Written by Nikolas Thornton

Edited by Dmitriy Beznosko and Keith Driscoll

Additional contributors: Fernando Guadarrama, Steven Mai

Please read the paper I developed this test for, Data Analysis Methods Preliminaries for a Photon-based Hardware Random Number Generator.

- Summary

- Visualization

- Line Counting

3.1 Horizontal Line Counting

3.2 Vertical Line Counting - Empirical Proof for Line Count Estimation

1. The Fractional Line Symmetry Test

The Fractional Line Symmetry Test (FLS Test) is a test that I developed specifically for my HRNG research that compares how frequently bits appear back-to-back horizontally and vertically when stacked and visualized into a 2D image. The folding done to stack and visualize the data is inherently random to the bitstream length itself. Once the linear bitstream is turned into a 2D image, the number of “lines” (back-to-back bits of some length) found horizontally and vertically should be the same. This test is sensitive to poor quality random numbers that otherwise pass tests like the standard deviation and average of the bitstream.

2. Visualization

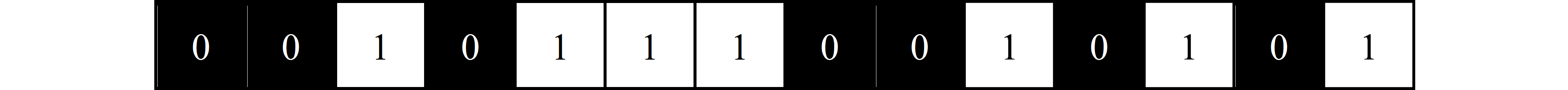

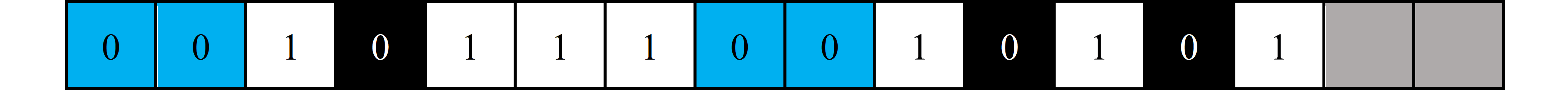

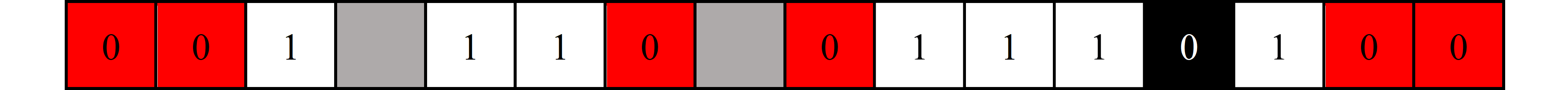

Visualization is done by first assigning the bits colors. 1s are white pixels and 0s are black pixels. Figure 1 shows an example for how the bits are initially visualized. The bitstream used in Figure 1 will be used for the rest of this section as an example.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 1. Bitstream example}} $$ To ensure that the bits will eventually be able to be stacked into a perfect square to form the 2D image, the length of the bitstream must be increased. These "nothing bits" that are added are not actually a part of the bitstream, and only used for the sake of visualization in the FLS Test. To achieve this, the ceiling of the square root of the bitstream length must be taken and squared as shown in Equation 1.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 1. Bitstream example}} $$ To ensure that the bits will eventually be able to be stacked into a perfect square to form the 2D image, the length of the bitstream must be increased. These "nothing bits" that are added are not actually a part of the bitstream, and only used for the sake of visualization in the FLS Test. To achieve this, the ceiling of the square root of the bitstream length must be taken and squared as shown in Equation 1.

$$ \operatorname{ceil}(\sqrt{14})^{2}=16 \ \ \ \ \ (1) $$

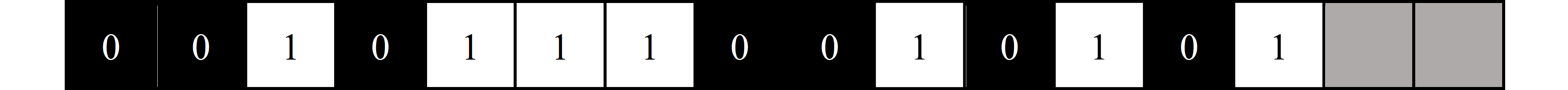

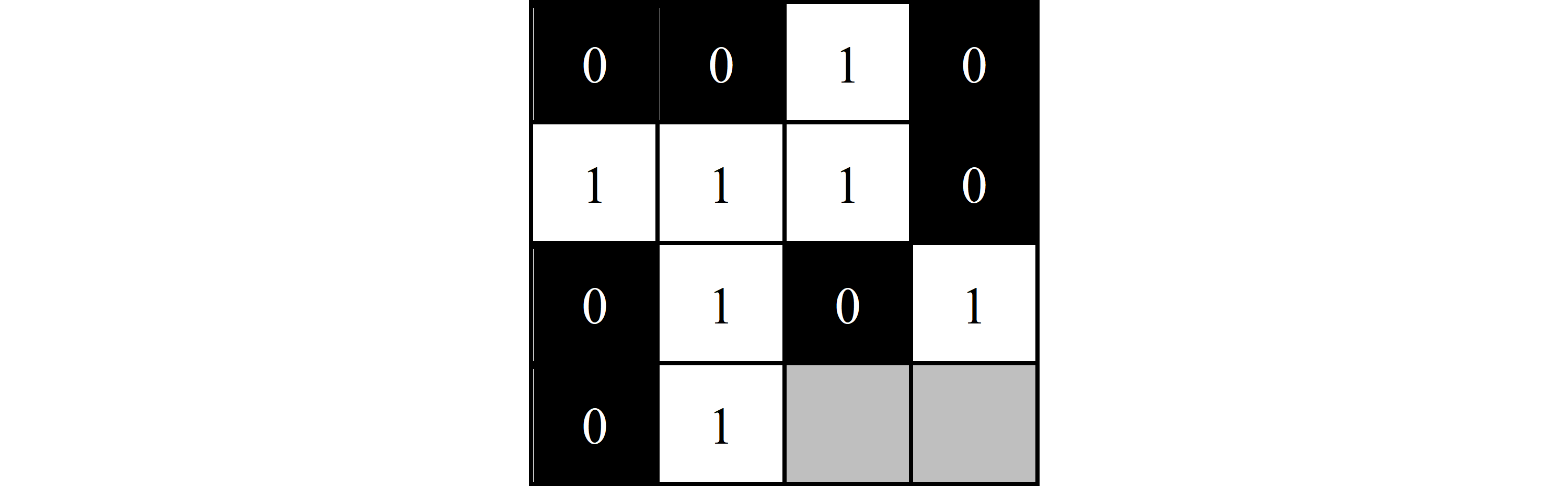

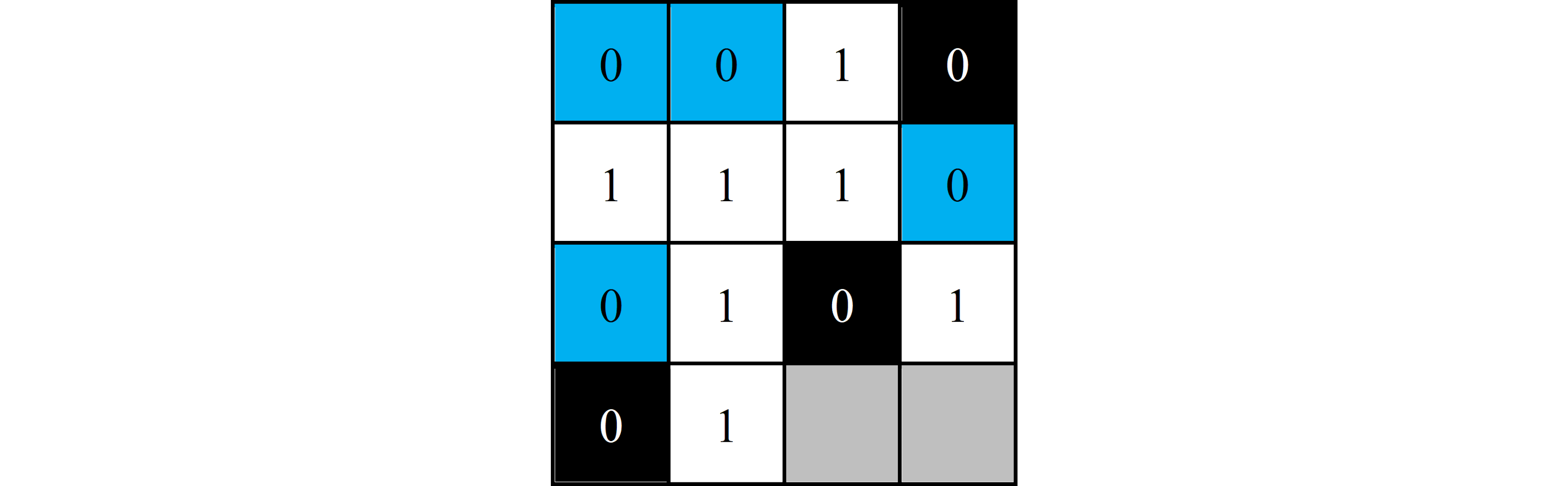

This means that $ 16-14=2 $ new "nothing bits" must be added to the bitstream, which for the sake of visualization are shown as grey pixels, as seen in Figure 2. Now that the bitstream length is a square number, it can be stacked left to right into a perfect square, as shown in Figure 3.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 2. Bits visualized with "nothing bits" added to the end}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 2. Bits visualized with "nothing bits" added to the end}} $$

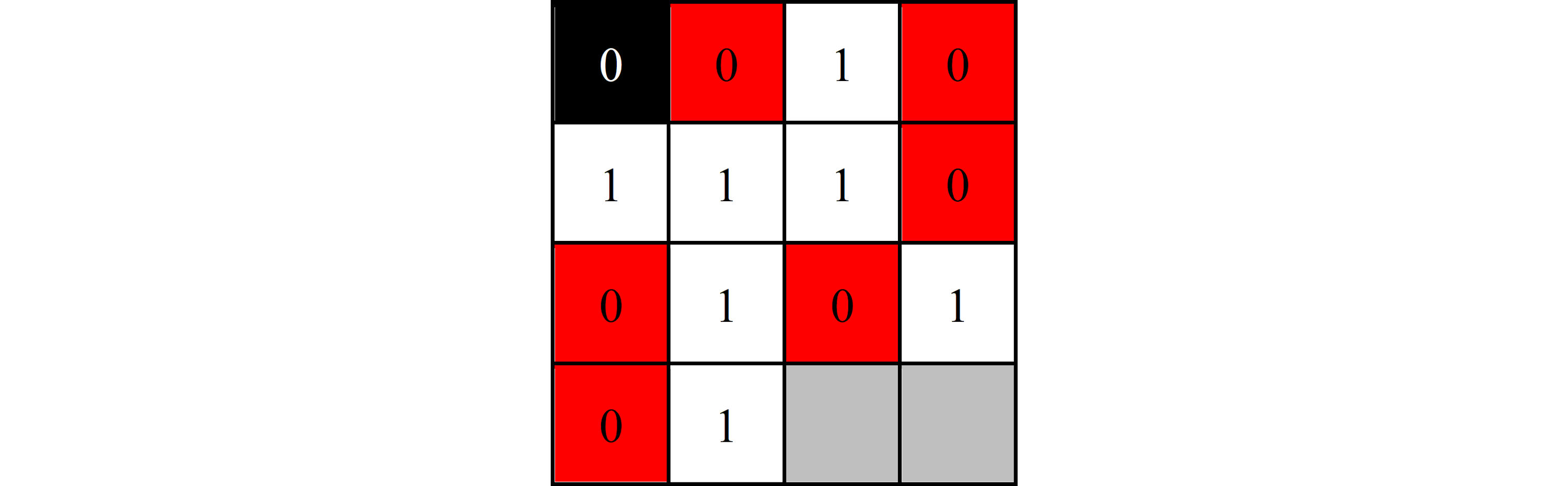

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 3. A bitstream stacked into a square image}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 3. A bitstream stacked into a square image}} $$

3. Line Counting

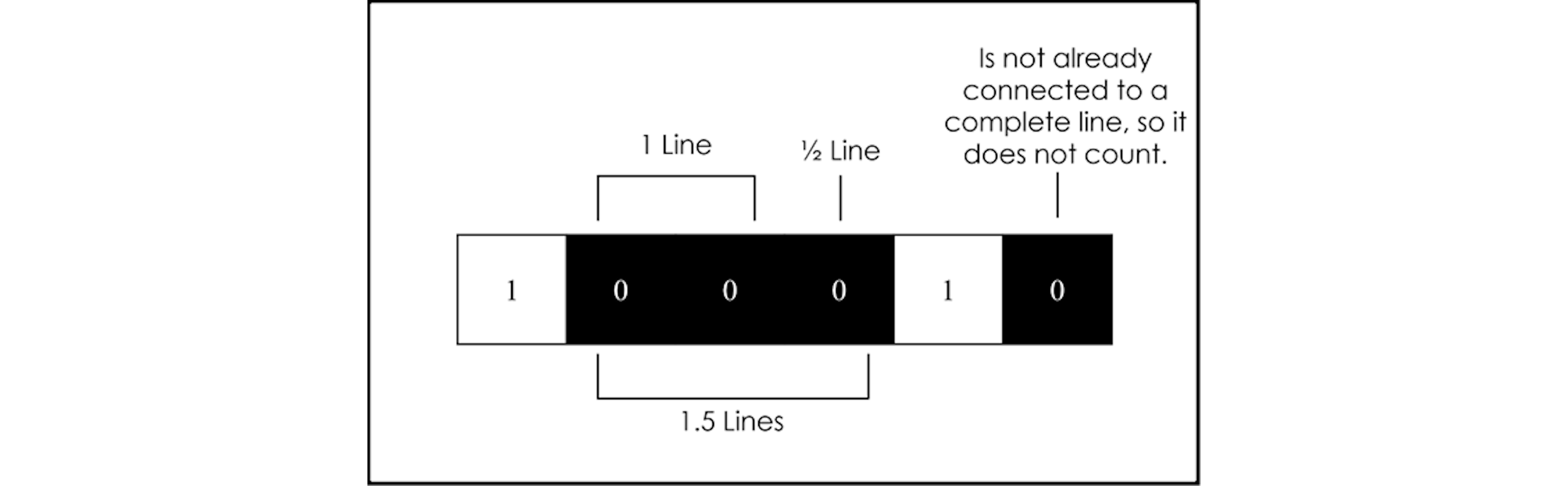

Line counting is the act of counting how many times a $1$ or a $0$ appears back-to-back a certain number of times in a row. How many times they must appear back-to-back before being considered one full line is called the $\text{detect length}$. It’s possible for bitstreams to have fractional lines. If a full line is found that has additional bits added towards the end, the additional bits are added to the total line count as $\frac{1}{ \text{detect length} }$. Using a different bitstream than what has been used in previous figures, Figure 4 illustrates line searching for zeros with a $\text{detect length}$ of $2$.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 4. How fractional lines are counted}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 4. How fractional lines are counted}} $$

3.1 Horizontal Line Counting

Horizontal line counting is easier than vertical line counting. For horizontal lines, the bitstream does not need to be stacked at any point. It can be read left-to-right linearly and searched for lines as described in Line Counting. Figure 5 shows the bitstream used in Figure 2 when line searched for zeros with a $\text{detect length}$ of $2$. The lines found are highlighted in blue. Figure 6 shows this bitstream when stacked and visualized, which demonstrates how the lines can cross the image-borders.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 5. Horizontal line counting for zeros with a detect length of two}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 5. Horizontal line counting for zeros with a detect length of two}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 6. Horizontal line counting when stacked and visualized}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 6. Horizontal line counting when stacked and visualized}} $$

3.2 Vertical Line Counting

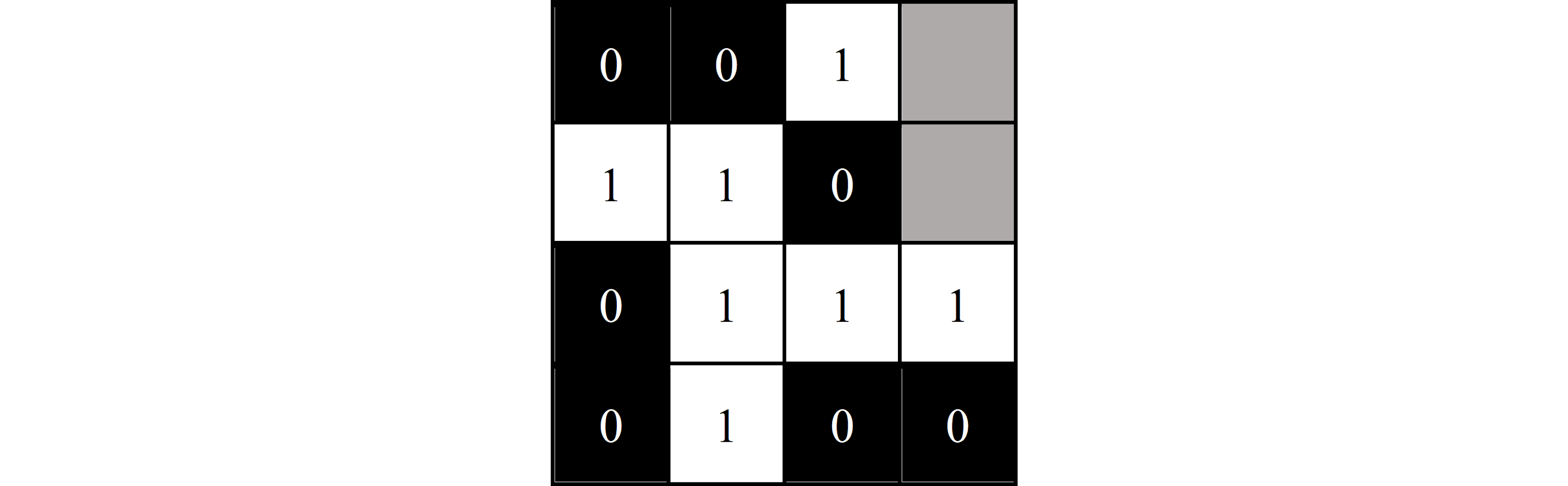

Vertical line counting is more difficult than horizontal line counting, as it requires that the bits are first visualized and stacked as shown previously in Figure 2. After the bits are visualized the resulting 2D image is rotated $90$ degrees counterclockwise as shown in Figure 7. From this, the bits are read left-to-right starting at the top left and unstacked into a linear bitstream. This is just the reverse of the visualization process described in Visualization. Figure 8 shows the bitstream after it has been unstacked.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 7. Visualized and stacked bitstream after being rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 7. Visualized and stacked bitstream after being rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise}} $$

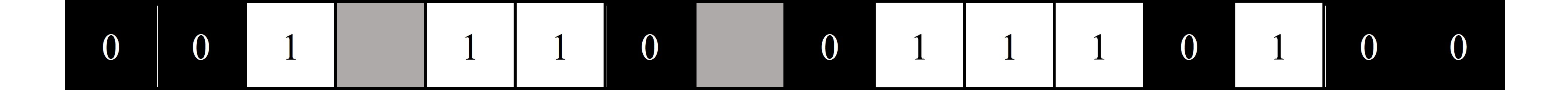

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 8. The bitstream after being unstacked}} $$ Now that the bitstream is linear, it can easily be searched for lines using the same method as horizontal lines. Figure 9 shows the bitstream after it has been line searched for zeros with a $\text{detect length}$ of $2$. The lines found are highlighted in red. Note that a grey "nothing bit" exists in between a line, but it does not stop it from being counted as a line. This bitstream can now be restacked into a square image, and then rotated back 90 degrees clockwise, as shown in Figure 10.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 8. The bitstream after being unstacked}} $$ Now that the bitstream is linear, it can easily be searched for lines using the same method as horizontal lines. Figure 9 shows the bitstream after it has been line searched for zeros with a $\text{detect length}$ of $2$. The lines found are highlighted in red. Note that a grey "nothing bit" exists in between a line, but it does not stop it from being counted as a line. This bitstream can now be restacked into a square image, and then rotated back 90 degrees clockwise, as shown in Figure 10.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 9. Unstacked bistream after being searched for lines}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 9. Unstacked bistream after being searched for lines}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 10. Vertical line counting when stacked and visualized}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 10. Vertical line counting when stacked and visualized}} $$

4. Empirical Proof for Line Count Estimation

It is possible to calculate the probability of how many lines should appear in a bitstream by using Equation Equation 2.

$$ \textrm{Lines} = \frac{n+1}{(2^{n+1})n} \times \textrm{bitstream length} \ \ \ \ \ (2) $$

where $n$ is the line search length and the bitstream length is the number of total bits in the bitstream.

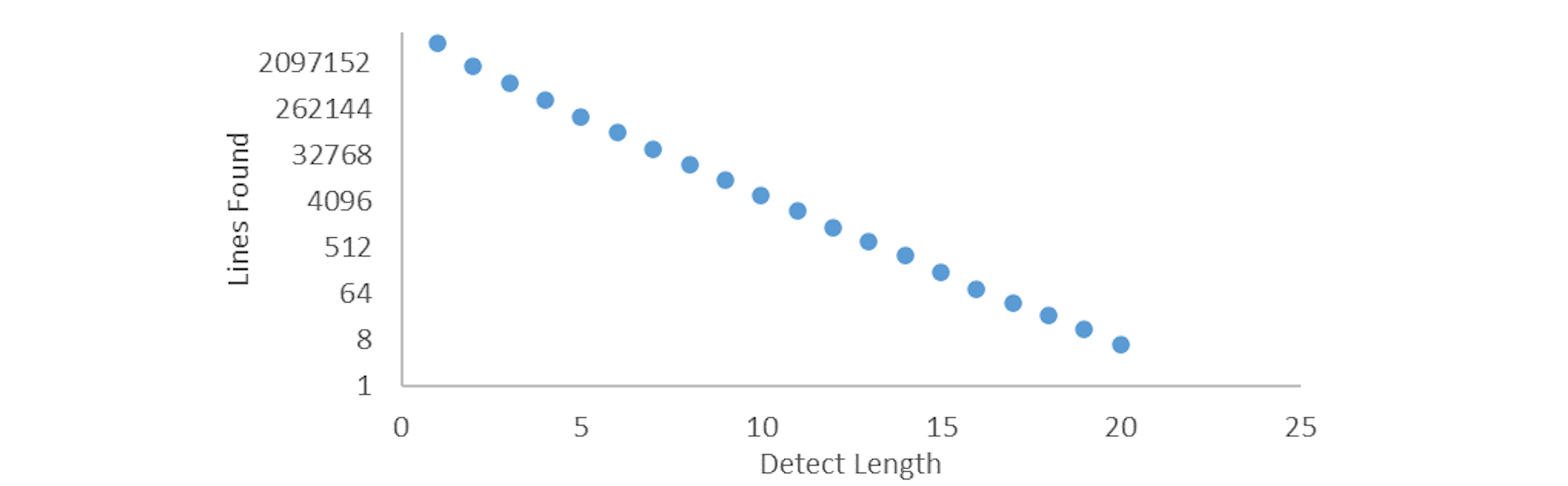

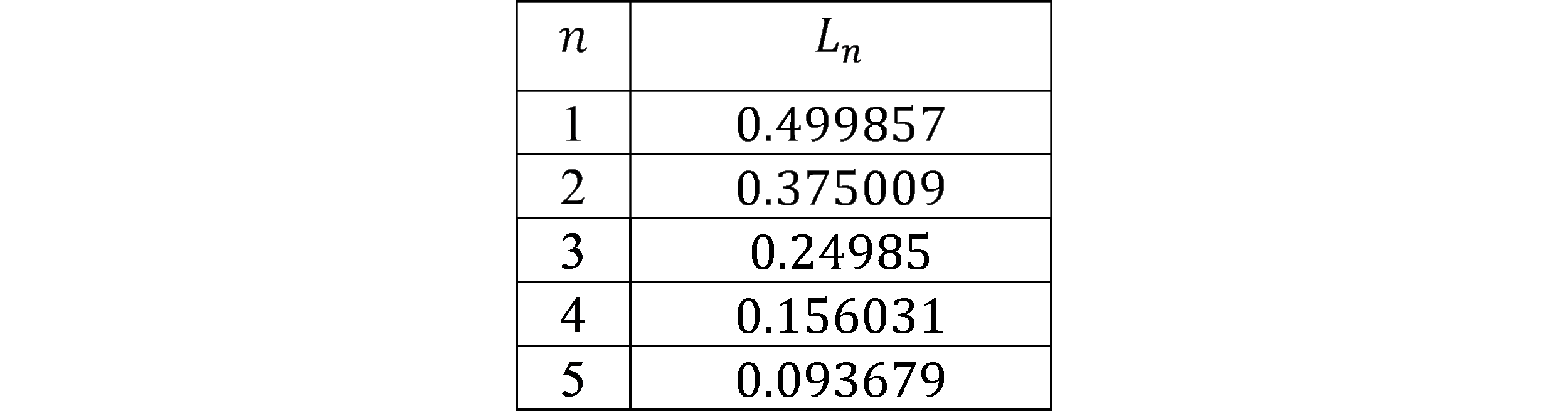

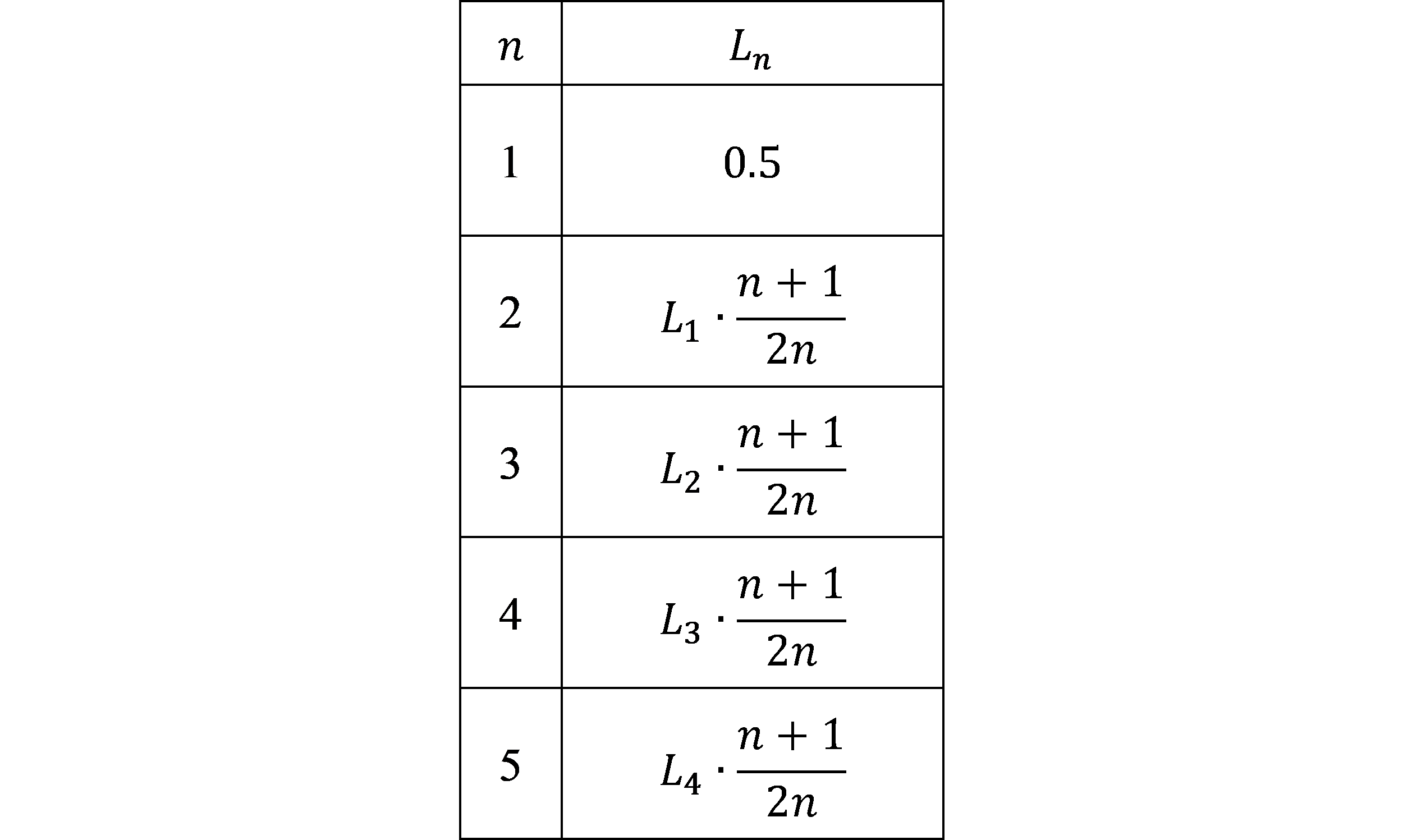

This equation was found by observing patterns in a bitstream of $10^7$ random bits generated using Python’s Random library. Figure 11. shows the number of lines detected for each detect length in these $10^7$ random bits on a base-2 logarithmic scale. By taking the lines found for each detect length, dividing them by the total number of bits in the bitstream, and multiplying them by the detect length, a series labeled $L_n$ is found as shown in Table 1.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 11. Number of lines detected in } 10^7 \textrm{ random bits for various detect lengths.}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Figure 11. Number of lines detected in } 10^7 \textrm{ random bits for various detect lengths.}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Table 1. The lines found divided by the bitstream length and multiplied by the detect length.}} $$

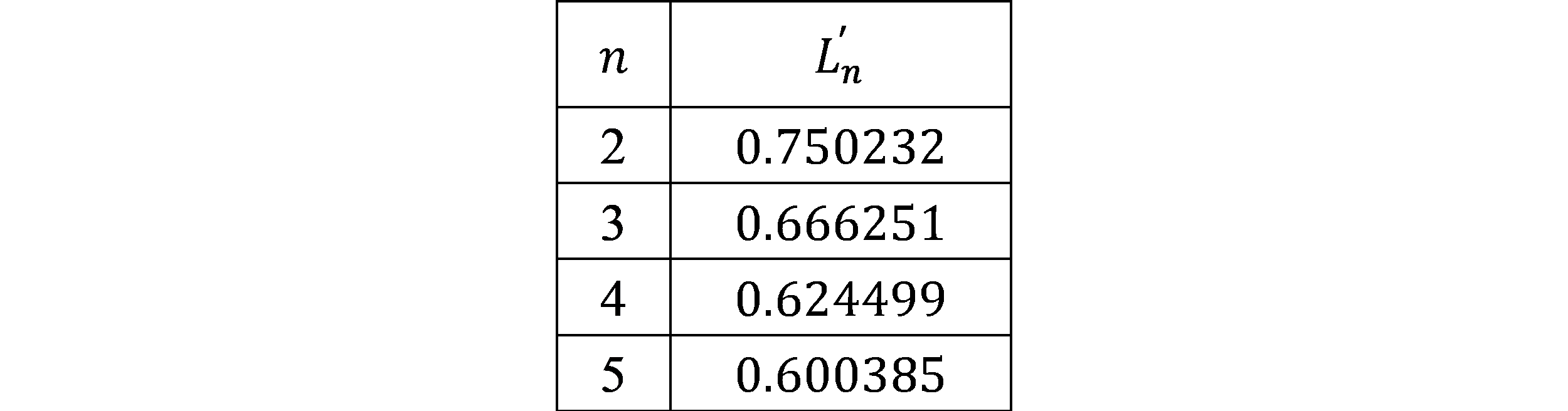

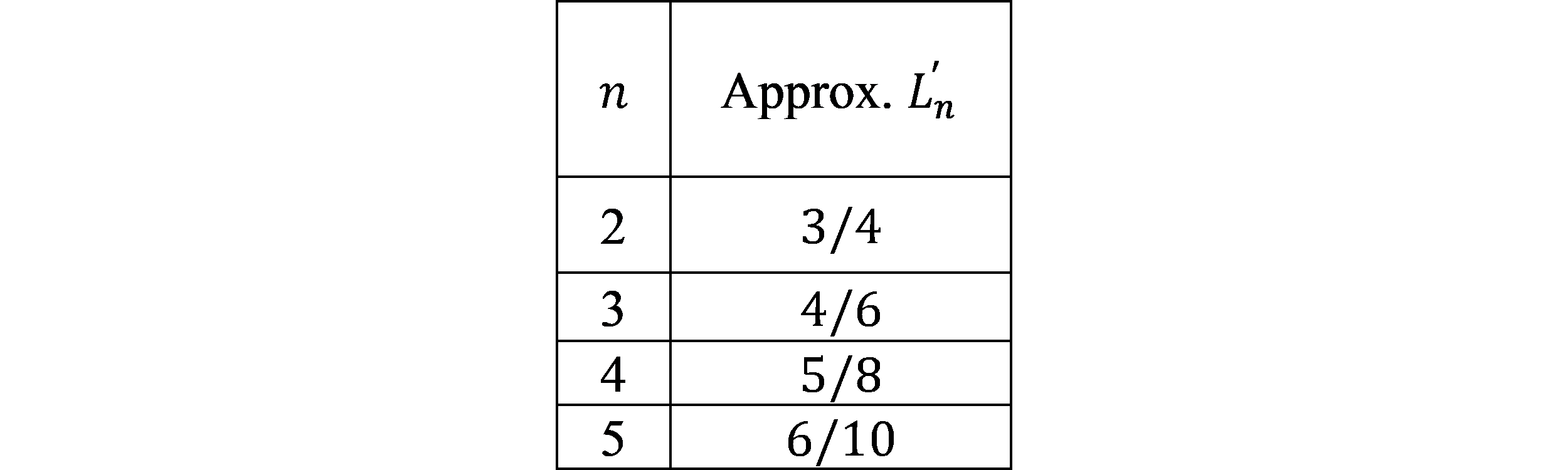

Table 1 only shows the first 5 items in the series. By taking each item in $L_n$ and dividing it by the previous item, a new series called $L' _ n$ is found as shown in Table 2. This series shows the percentage change of each item when compared to the previous. This series starts at $n=2$ as there is nothing for $L_1$ to divide by. This series is notable as it can roughly be approximated as simple fractions, as shown in Table 3.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Table 2. } L_n' \textrm{ showing the percentage change of each item.}} $$

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Table 3. Data from Table 2 approximated as fractions.}} $$

These fractions, rather notably, are observed to follow the form of Equation 3.

$$ \frac{n+1}{2n} \ \ \ \ \ (3) $$

Using the percentage change of Equation 3 between the values in $L_n$, the result shown in Table 4 is found. Note that $L_1$ is included despite not having an $L_0$ to be multiplied by. This is because given a random bitstream of any size, the number of bits found for a detect length of 1 divided by the bitstream size is always $1/2$.

$$ {\scriptsize \textrm{Table 4. } L_n \textrm{ as expressions of the percentage change between values.}} $$

It is noted that this new definition of $L_n$ defines every item as a multiple of all of the previous items. This when expanded is shown in Equation 4.

$$ L_{n}=0.5\cdot\frac{i+1}{2i}\cdot\frac{i+2}{2(i+1)}\cdot\frac{i+3}{2(i+2)}\cdot...\cdot\frac{i+(n-1)}{2\cdot{(i+(n-2))}} \ \ \ \ \ (4) $$ where $i$ is equal to the value of $n$ taken from its earliest use in the series, which in this case is $L_2$, but it will be left as $i$ for now. From this, all instances of $(i+x)$ in every numerator can be canceled using the next term’s denominator. This means, however, that the first term retains its denominator, and the last term retains its numerator as visible in Equation 5 and Equation 6.

$$ L_{n}=0.5\cdot\frac{\require{enclose}\enclose{horizontalstrike}{i+1}}{2i}\cdot\frac{\require{enclose}\enclose{horizontalstrike}{i+2}}{2(\require{enclose}\enclose{horizontalstrike}{i+1})}\cdot\frac{\require{enclose}\enclose{horizontalstrike}{i+3}}{2\require{enclose}\enclose{horizontalstrike}{(i+2)}}\cdot...\cdot\frac{i+(n-1)}{2\cdot\require{enclose}\enclose{horizontalstrike}{{(i+(n-2))}}} \ \ \ \ \ (5) $$

$$ L_{n}=0.5\cdot\frac{1}{2i}\cdot\frac{1}{2}\cdot\frac{1}{2}\cdot...\cdot\frac{i+(n-1)}{2}=0.5\cdot\frac{i+(n-1)}{2^{n-1\ }i} \ \ \ \ \ (6) $$

For the next step, the variable $i$ can be replaced with its known value of $2$ to produce Equation 7.

$$ \frac{0.5\cdot\frac{n+1}{2n}}{n}=\frac{0.5\cdot(n+1)}{2^{n}n}=\frac{n+1}{(2^{n+1})n} \ \ \ \ \ (7) $$

Finally having a general form for $L_n$, an equation to get the probability of lines appearing for any detect length can be found by simply undoing the multiplication of detect length done to create $L_n$ in the first place, as shown in Equation 8.

$$ L_{n}=0.5\cdot\frac{2+\left(n-1\right)}{2^{n-1}\left(2\right)}=0.5\cdot\frac{n+1}{2n} \ \ \ \ \ (8) $$

This yields the decimal probability of lines being found for any $\text{detect length}$ of $n$, but needs to be multiplied by the $\text{bitstream length}$ to determine exactly how many lines are found for any bitstream size. Multiplying the above equation by the $\text{bitstream length}$ yields Equation 2, as re-iterated below.

$$ \textrm{Lines} = \frac{n+1}{(2^{n+1})n} \times \textrm{bitstream length} \ \ \ \ \ (2) $$

Thank you for reading! Another possible use of the FLS Test is diagonal-line counting, as originally conceptualized by my fellow contributor, Fernando Guadarrama. Check out my article on a diagonally wrapping traversal algorithm for a possible diagonal FLS Test implementation. Also be sure to check out the original paper I wrote this for here.